How is inequality in America produced and reproduced?

How do class, race and gender interact?

How do educational opportunities and disadvantages, family structure and incarceration combine to produce the massively unequal society that we inhabit?

Our understanding of the structures and mechanisms of inequality in the US today is being transformed by the construction of large institutional datasets based on records from the tax administration and other similar public data-gatherers. Studies of educational mobility have already had a huge impact. But now the biggest of these projects – the Equality of Opportunity Project – has turned to squarely address the question of race.

The results produced by Raj Chetty, (Stanford University and NBER), Nathaniel Hendren (Harvard University and NBER), Maggie R. Jones (U.S. Census Bureau) and Sonya R. Porter (U.S. Census Bureau) are astonishing in their stark clarity. The New York Times team of Emily Badger, Claire Cain Miller, Adam Peace and Kevin Quealy have ably summarized the results and added brilliant graphics.

If you read just one thing on American society and inequality today, this week, this month or even this year make it this New York Times essay as well as the underlying report, slides and summary. This is indispensable material for the debate about the state of American society today.

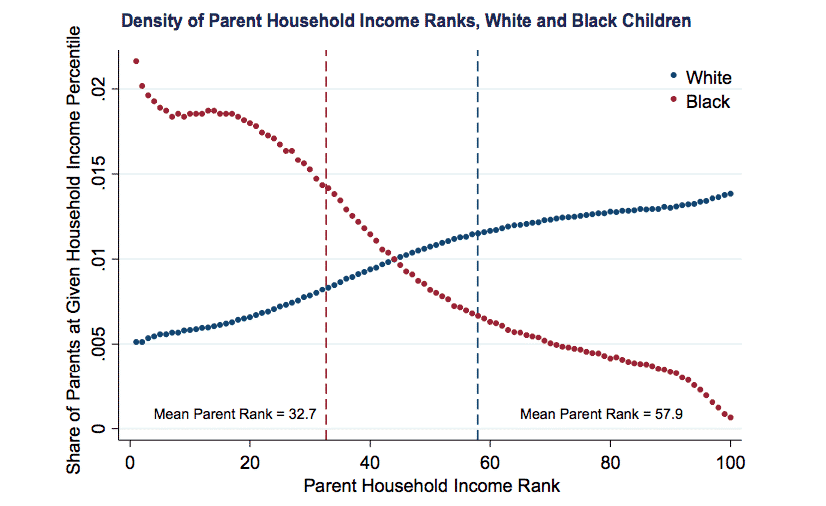

Black and white families have very different levels of income and wealth. The white population is spread across the entire distribution. Black families are clustered at the bottom end.

Source: Chetty et al 2018

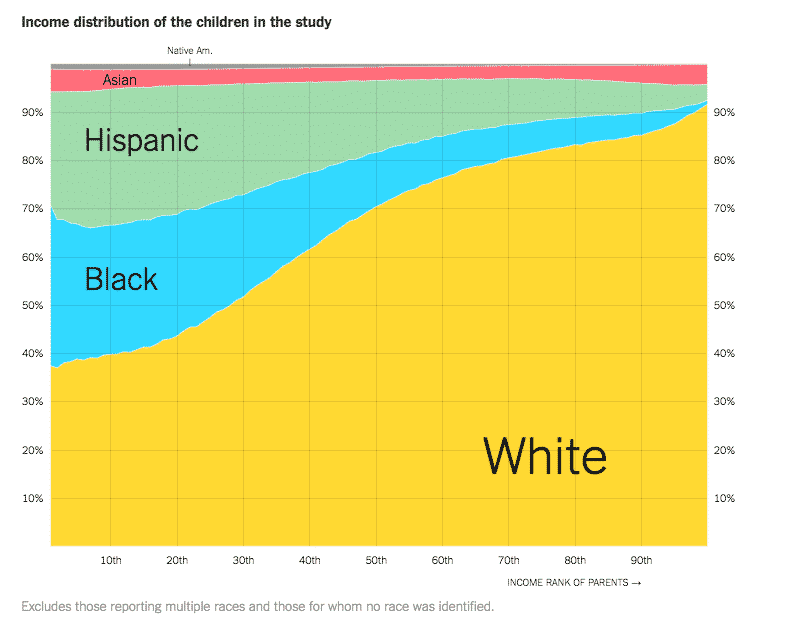

This means that of all children growing up poor in America in the last decades, at least a third are black, whereas only 1 % of those growing up at the top of the income pyramid are. Hispanics make up another 25 percent of low income families and whites account for c. 37 percent.

Source: Badger et al 2018

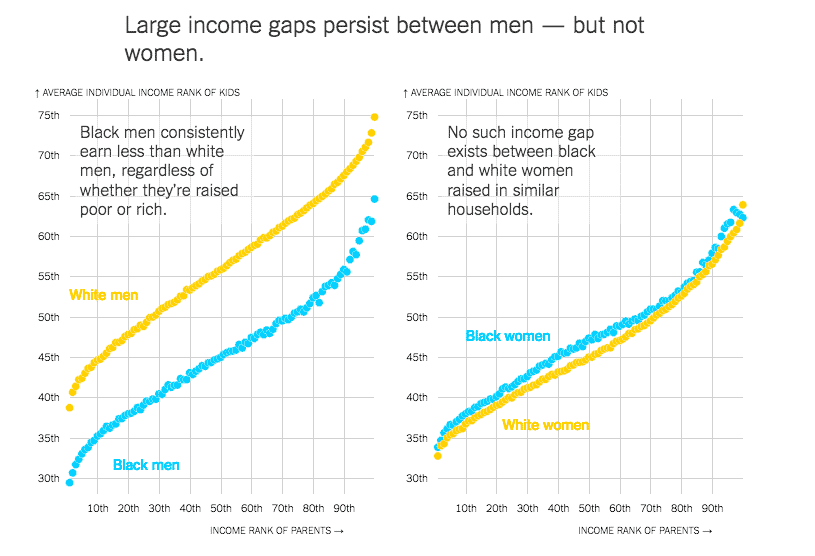

This difference in starting positions affects all black Americans. But it affects black women and men differently.

For any given parental income level black women in their 30s (despite being disproportionately single mothers, having slightly lower high school completion rates and more disciplinary issues at high school) achieve income levels slightly greater than their white counterparts. Black women work at similar rates, for similar pay and for similar hours as their white counterparts. They are also in similar occupations.

Source: Badger et al 2018

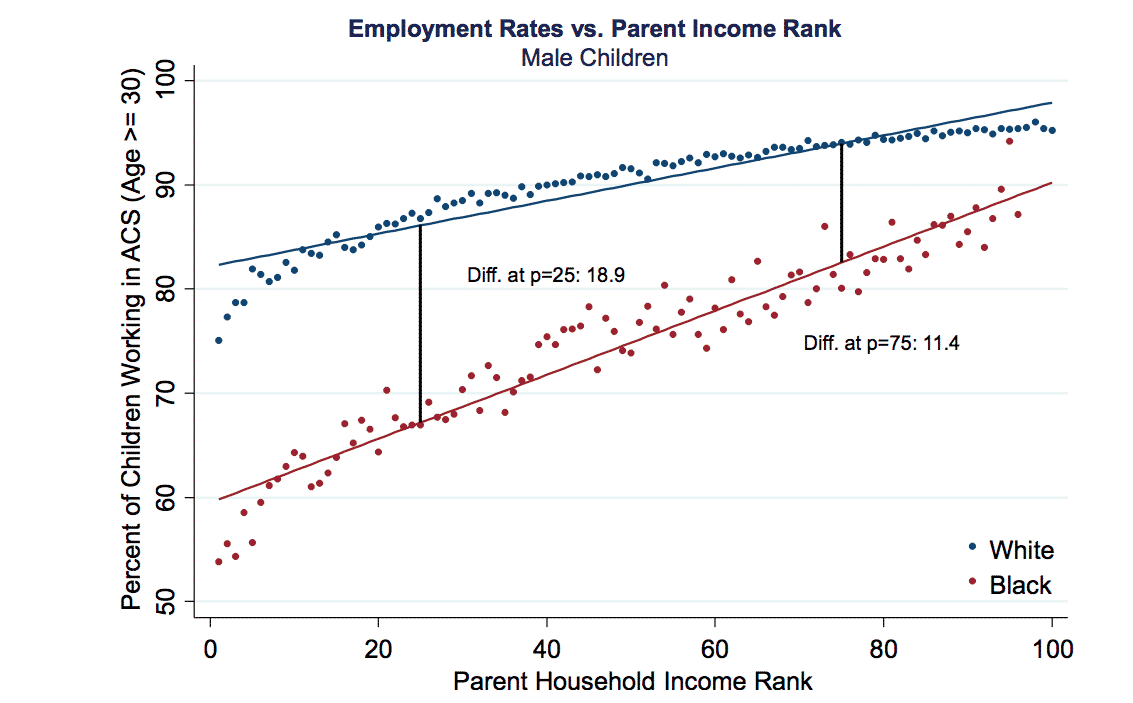

By contrast, black men, whether their family background was hard up or comfortably off, earn significantly less than their white counterparts. The employment rates for black men in their early 30s from lower income backgrounds, are dramatically lower than for their white counterparts and across the board, regardless of class background, their is a gap in hourly earnings.

Chetty et al 2018

This is an astonishingly stark result. For American women it may be reasonable to say that at a first approximation (and at a first approximation only) class trumps race. They struggle to overcome the huge disadvantage of being born disproportionately into the bottom of the income pyramid, but they succeed (and fail) at the same rates as their white counterparts.

For black men that is not true. For them gender and race combine to produce a structure of socio-economic disadvantage that is essentially racialized (and gendered).

The disadvantage starts early. For young black men, high school drop out rates are far higher than for their white counterparts at any given level of income. They are far more likely to be cited for disciplinary violations at school. But if one wanted to point to a single variable to explain the stunted mobility of black men, it is the disastrously lopsided operation of US criminal justice system.

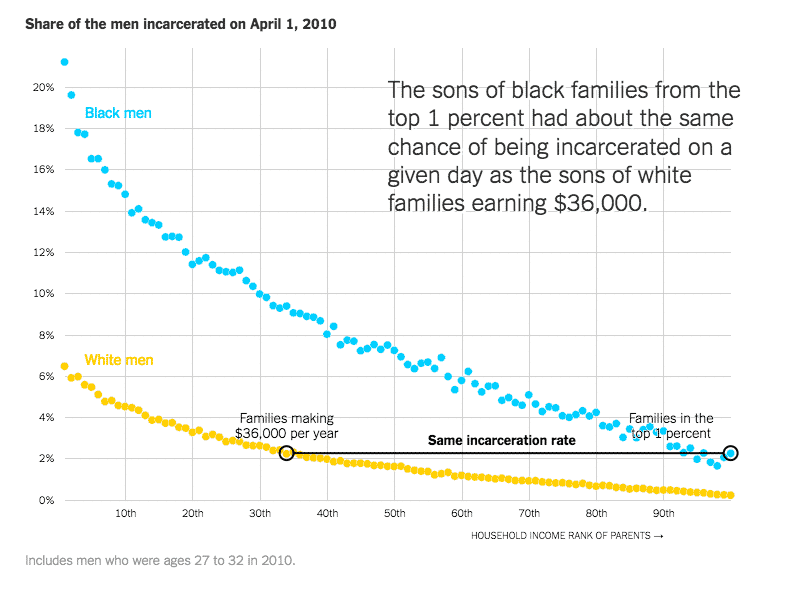

Incarceration rates vary by income for both white and black Americans. But the chances of the son of a rich black family ending up in prison are the same as that for lower middle-class white Americans.

Source: Badger et al 2018

In April 2010, 21 percent of black men in their thirties born into low income families were in jail or prison. Of course, many of those men are subsequently released and others are incarcerated in their stead. But the ex-inmates carry the social scars for the rest of their lives.

For black and white women for any given parental income level there is no difference in incarceration rates.

Introducing the gender variable allows the researchers to dispose of the question of IQ and test scores. Black men and women score very similarly on all such tests and yet despite their lower score than white women, black women match their white counterparts in social mobility. Whatever it is that the tests are measuring, it is not the aptitudes that matter for inter-generational income mobility.

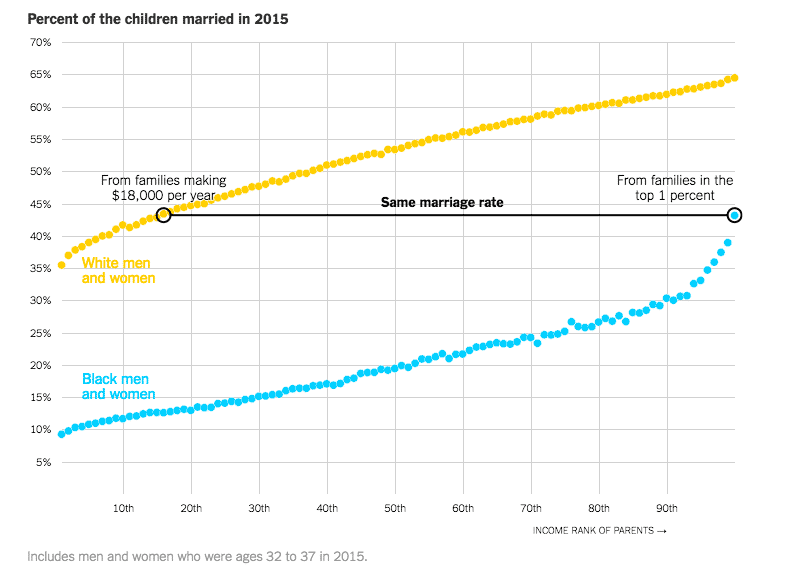

Does family structure matter? 70 percent of black children are born outside marriage. At any given income level white men and women marry far more than their black counterparts. Do these differences have an impact on inter-generational mobility?

Source:Badger et al 2018

Not according to the study. The study shows that the marital and educational qualifications of the households that black and white kids grow up in, have a very limited impact on differential adult income levels. What does matter is not the particular characteristics of a black family (marital status, parental education etc), but the community that family is living.

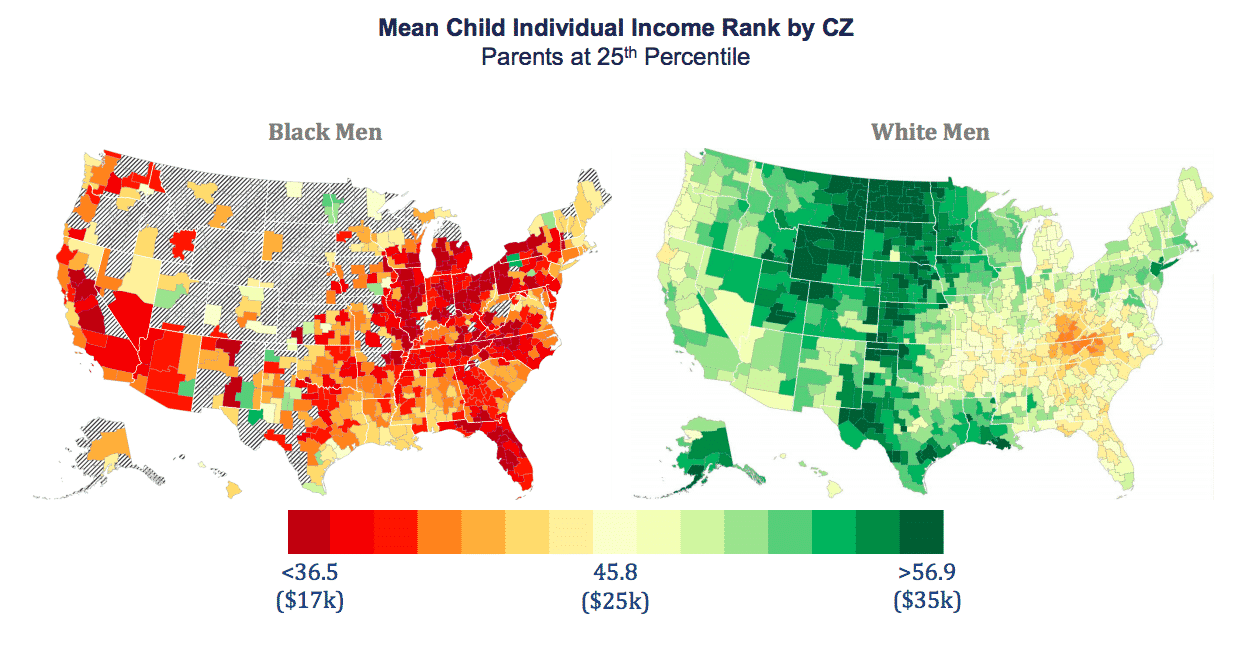

Source: Chetty et al 2018

For white men there are large parts of the US where mobility is positively enhanced. For black men there are very few such communities and there are large swaths of the US, notably the South East, the postindustrial midwest and parts of California, which systematically diminish black men’s life chances.

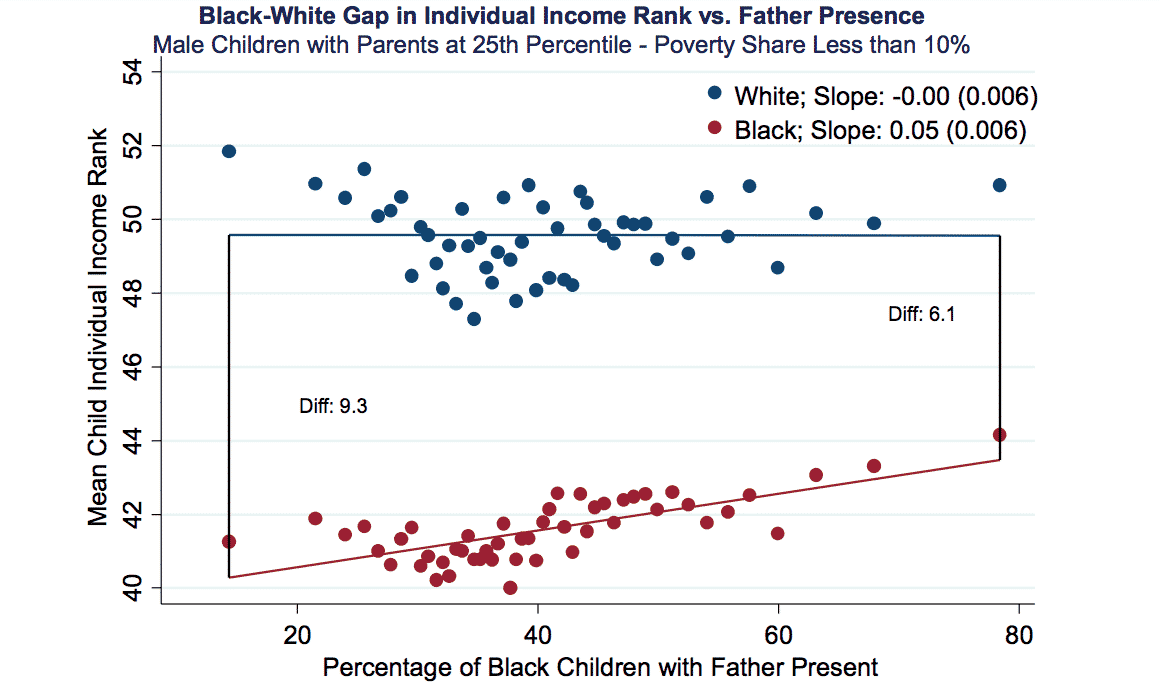

Once we go down to the census tract level this basic finding is reinforced. But the research also finds that in high income neighborhoods that promote mobility for both white and black men, the gap between the races is larger. Within such low-poverty, high success neighborhoods what tends to lower the racial gap is the presence of fathers of black children and lower levels of racial prejudice. It is not the presence of men, or even a particular child’s father, but the presence of fathers as such that has a positive impact on black boys’ prospects.

Source: Chetty et al 2018

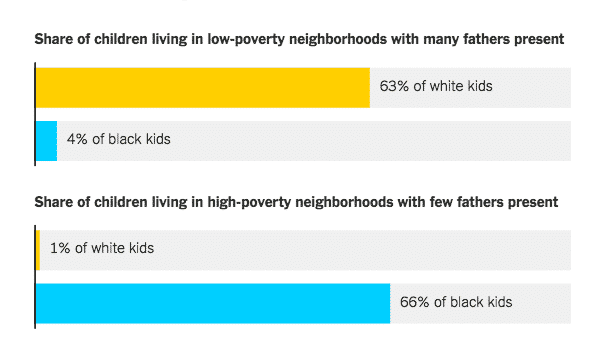

The tragedy is that very few black boys born into low income families grow up in communities that offer them these essential conditions for success. The chances of young black men growing up in communities blighted by poverty and the absence of paternal role models are vastly higher than for their white counterparts.

Source: Badger et al 2018

Almost two-thirds of white Americans in their 30s today grew up in neighborhoods with low rates of poverty and families with most fathers present. Four percent of black Americans did. By contrast two-thirds of thirty-something black Americans spent their childhood in neighborhoods of high poverty and low paternal presence. By contrast only 1 percent of white Americans suffered those disadvantages.