Prospect is publishing an essay next week on the anniversary of the failure of the Northern Rock bank in Britain in the late summer and early autumn of 2007. In the piece I try to place both the Northern Rock crisis and subsequent events in US in a broader frame.

The financial meltdown of 2007-8 was centered on the US. But it was emphatically not an exclusively American affair. Somewhere between 25 and 30 percent of US mortgage backed securities, depending on how you count and which mortgages you focus on were owned by foreign investors. The Chinese held the securities guaranteed by Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae. The Europeans held a huge slice of the more adventurous and risky private-label MBS. They were the leading force in sponsoring Asset Backed Commercial Paper vehicles.

The problem in 2008 was not just that the underlying mortgages were going bad. The more urgent issue was how the Europeans had funded their balance sheets. The sobering conclusion of the BIS was that at least $ 2 trillion were funded on an extremely precarious basis. Roughly $ 1 trillion were funded by money borrowed from America’s money market mutual funds. Another $ trillion were scrambled together from inter bank borrowing, swapping Euros, sterling and other foreign currencies into dollars and borrowing central bank reserves.

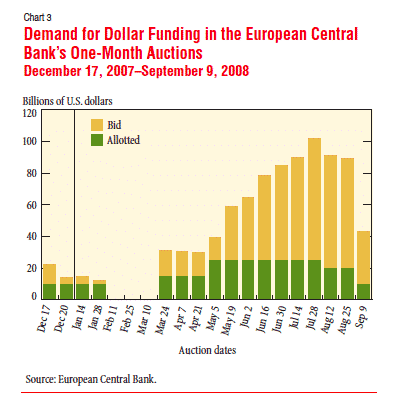

From August 2007 those interbank and short-term money market funding sources began to shut down. This affected banks on both sides of the Atlantic but it created a specific issue for the European banks whose overseeing central banks did not have limitless capacity to issue dollar liquidity, at least until the crisis. The reserves held by the Bank of England, the ECB and the Swiss National Bank were astonishingly small relative to the size of their financial sectors and the multinational balance sheets of their banks.

source: https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/research/current_issues/ci16-4.pdf

The risk that arose from this funding gap was that the European banks would be forced into a massive fire sale of dollar assets. In the process they would have suffered major losses and would have undone any effort by the US authorities to stabilize their markets.

How was this funding gap to be closed? The largest European banks with branches in New York could be supplied with liquidity directly by the Fed. And the Fed did so on a huge scale. European banks were treated on the same basis as American firms.

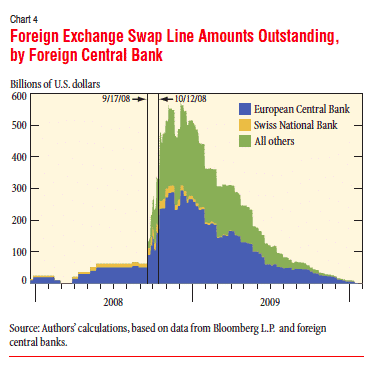

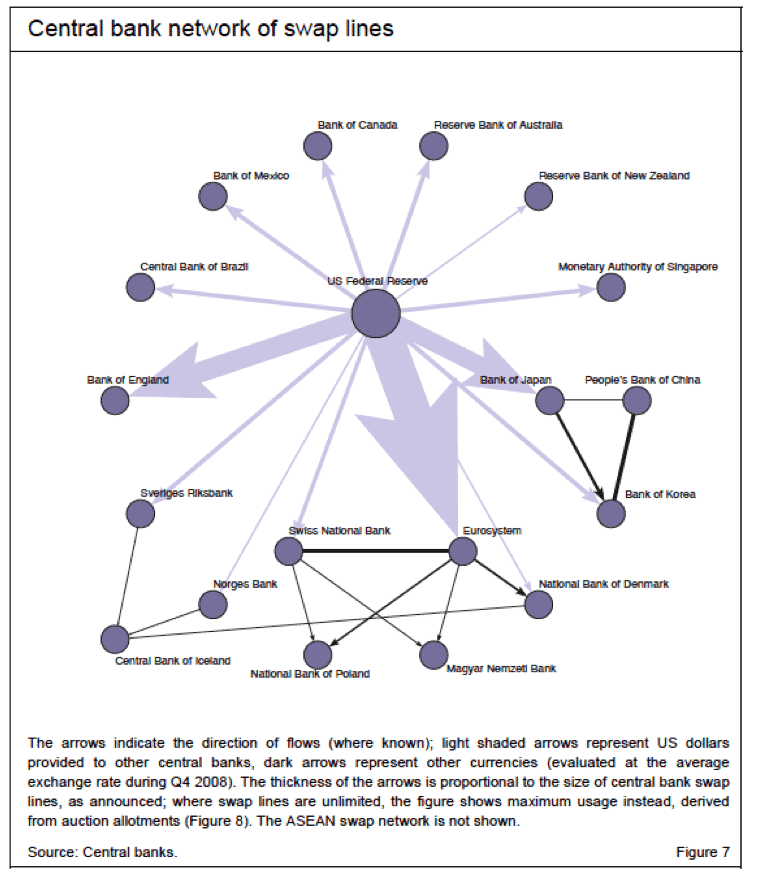

But even this was not enough. To supplement these measures the Fed activated the so-called swap lines, exchanges of currency through which the Fed supplies other central banks with easy access to dollar funding so that they in turn might supply the dollar funding needs of their overgrown banks. Though they have a history in trans-Atlantic finance, they had never been used on this scale before. They are the great institutional innovation of the financial crisis of 2008 and its aftermath.

The scale of Fed swap activity was enormous.

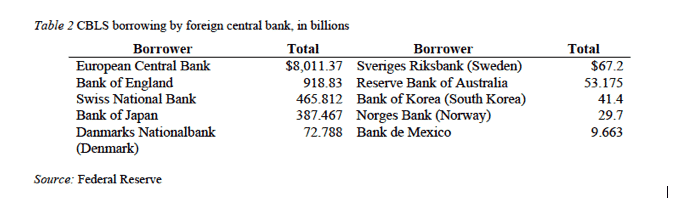

The total sums borrowed and repaid by the leading central banks were gigantic.

Source: http://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/wp_698.pdf

This crisis of dollar-funding and the actions taken by the central banks to contain the problem is the great “untold” story of the crisis. It will form a major strand in my forthcoming book, Sudden Stop, out in 2018.

Of course the dollar-funding drama and the swap lines are no secret to those involved. Amongst specialists, avid readers of BIS publications etc they are widely discussed. The swap lines are a subject of great fascination for specialists in international political economy, international monetary economics etc. One of the first on the case was Perry Mehrling with a blog post already in November 2008 and a stream of publications since. Zero hedge was all over the story. But in the larger narratives of the financial crisis and the Fed’s response they have been assigned a minor place. Why this imbalance?

- The swap lines are technical instruments, which viewed on their face might regarded as nothing more than an administrative nicety. They were all properly accounted for. The Fed held collateral at all times. It made a nice profit on the business. “There is nothing to see here!”

- More importantly I am convinced that they are displaced to the margins of our narratives of the crisis, by the prevailing interpretation of the crisis as a series of national events. Once the crisis was revealed to be not about the Sino-American imbalance, it was no longer seen as an event associated with globalization. If it was basically a crisis internal to American society and politics, an interpretation which the Europeans were only too happy to agree with, the problem that the swap lines targeted shifts out of focus – the acute dollar funding problem of the European banks.

- Furthermore, the central bankers involved were happy for their transnational liquidity support measures stay outside the public eye. Political support for domestic banks is hard enough to legitimize. Huge liquidity actions designed to support foreign central banks and foreign banking systems were not something that the Fed wanted to pitch to Congress in 2008 or at any point after that.

And yet since October 2013 the swap lines have been made permanent. The key central banks now have standing arrangements to issue currency to each other in unlimited amounts. As Mehrling likes to say: “Forget the G7, Watch the C6.”

Anyway, this is more context for the Prospect story. Check it out.

Anyway, this is more context for the Prospect story. Check it out.